CSS to speech: alternative text for CSS-generated content

|

Changelog

- Despite the fact that Chrome exposes the alt text of a CSS image as part of the accessible name of the element it is used on, James Scholes shared that the alt text is not announced by NVDA, which means that screen reader users using this popular browser-screen reader combination will miss out on meaningful information.

- Removed the phrase that said that implied that CSS psuedo-elements are not exposed the same way that HTML elements are exposed in the accessibility tree. Chrome and Firefox now do expose pseudo-elements in the accessibility tree.

The CSS ::before and ::after pseudo-elements are used to insert presentational content before and after (respectively) existing content in an HTML element.

The content property is used to define what content is inserted in these elements.

For example, the following CSS adds the text "Error: " before the content of an error message container:

<div class="error-message">The value you entered is invalid.</div>.error-message::before {

content: "Error: ";

}This example adds an SVG chevron icon to a button that toggles the display of some content:

<button class="disclosure-widget">License Agreement</button>button.disclosure-widget::before {

content: url("data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg height='24' viewBox='0 0 24 24' width='24' xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%3E%3Cpath d='m8.586 5.586c-.781.781-.781 2.047 0 2.828l3.585 3.586-3.585 3.586c-.781.781-.781 2.047 0 2.828.39.391.902.586 1.414.586s1.024-.195 1.414-.586l6.415-6.414-6.415-6.414c-.78-.781-2.048-.781-2.828 0z'/%3E%3C/svg%3E");

width: 1em;

height: 1em;

}This example adds the ↗ unicode character to indicate that the anchor links to an external resource or opens in a new tab or window:

<a href="..." target="_blank" class="external">CSS Generated Content specification</a>a.external::after {

content: " \2197" ; /* ↗ = North East Arrow */

}The contents of CSS pseudo-elements is exposed as part of the content of the element it is inserted into. And, importantly, CSS content takes part in the accessible name computation of the element they are used on.

CSS pseudo-content in the accessible name computation algorithm

When the browser needs to determine the accessible name of an element, it uses an algorithm called “Accessible Name and Description Computation” algorithm.

According to the specification: when an element’s name is derived from its contents, the browser must include the textual contents of CSS pseudo-elements in the accessible name. This includes the contents of the ::before and ::after pseudo-elements, as well as the ::marker when an element supports ::marker.

Check for CSS generated textual content associated with the current node and include it in the accumulated text. The CSS

:beforeand:afterpseudo elements can provide textual content for elements that have a content model.

- For

:beforepseudo elements, User agents MUST prepend CSS textual content, without a space, to the textual content of the current node.- For

:afterpseudo elements, User agents MUST append CSS textual content, without a space, to the textual content of the current node.

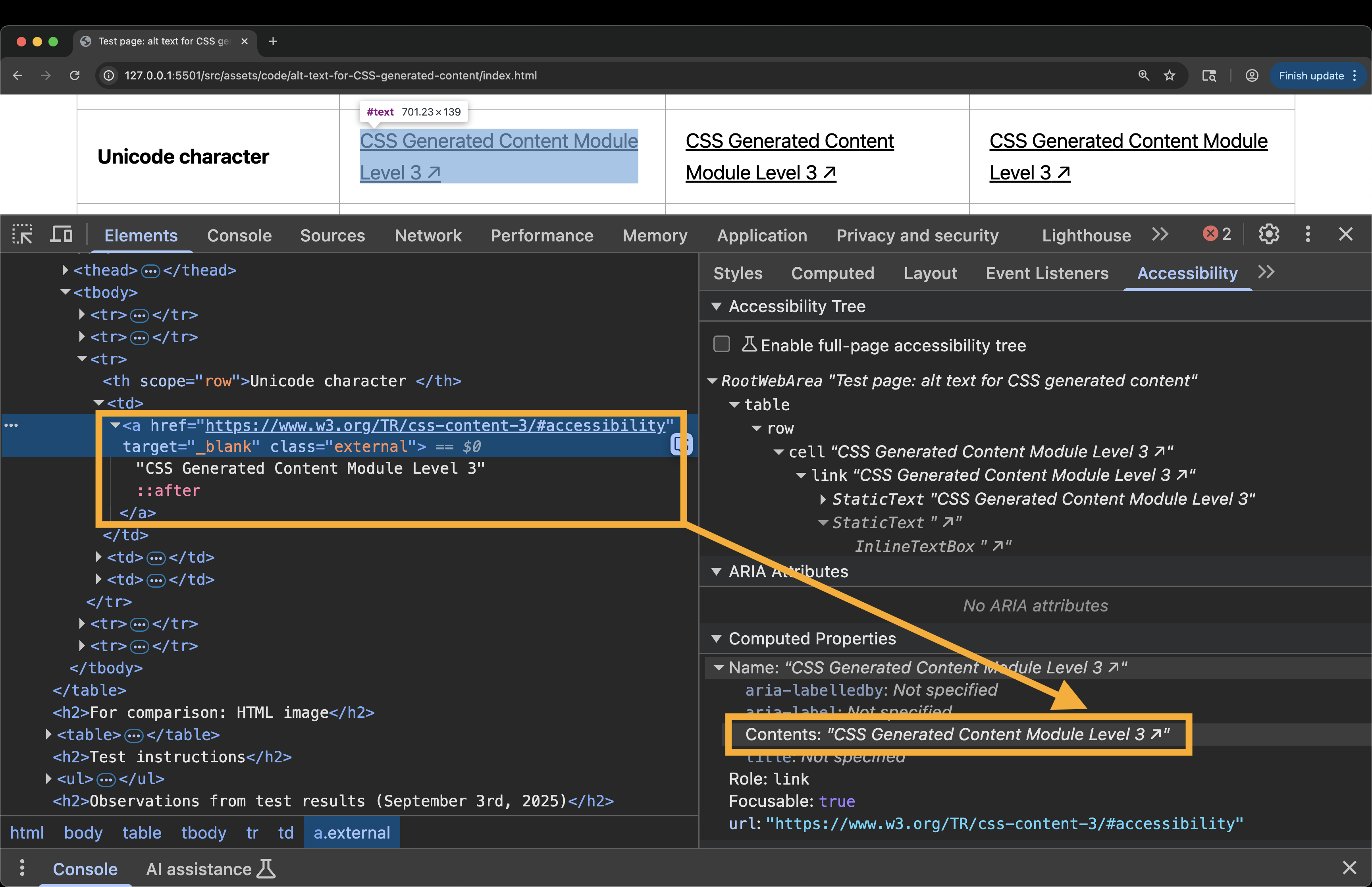

For example, if we look at the link from the example in the previous section:

<a href="..." target="_blank" class="external">CSS Generated Content specification</a>a.external::after {

content: " \2197" ; /* ↗ = North East Arrow */

}…the accessible name for the link is going to be “CSS Generated Content specification ↗”. If you open the browser DevTools and check the accessibility information of the link, you will see the unicode character included in the accessible name.

The name of the link will be read by a screenreader as “CSS Generated Content specification North East Arrow” or “CSS Generated Content specification Upright Arrow”. The screen reader announces the unicode character by its default alternative text, which does not commnunicate the intended meaning of the character.

Images and characters inserted in CSS should be treated the same way you treat HTML images: when an image (or character) is meaningful, it must be described to assistive technology (AT) users using alternative text that communicates its purpose. This ensures that AT users are getting the same information as sighted users.

Providing descriptive alternative text to meaningful images is a WCAG requirement.

In HTML, you provide the alternative text of an image in the <img>'s alt attribute:

<img src="/path/to/meaningful/image.jpg" alt="[ the text describing the purpose of the image to someone who can't see the image ]">On the other hand, when the image is purely decorative, it should be hidden from screen readers and excluded from an element’s accessible name to avoid unnecessary or confusing announcements.

In HTML, an image is marked as decorative by giving it an empty alt text. The empty alt value ensures that the image is not exposed and announced by screen readers:

<!-- When the image is decorative, leave the alt text empty. -->

<img src="/path/to/decorative/image.png" alt="">But how do you provide alternative text to CSS-generated content to make sure it is announced (or not announced!) as expected?

Alternative text for CSS generated content

Historically, there hasn’t been a standard way to provide alternative text for CSS generated content and images. So, we resorted to creating placeholder <span>s in the markup for this purpose.

For decorative CSS content, we inserted the content into a <span> and then used aria-hidden="true" to hide that <span> from screen reader users.

<a href="..." target="_blank" class="external">

CSS Generated Content specification

<span aria-hidden="true" class="icon"></span>

</a>a.external .icon::before {

content: " \2197";

}And to provide descriptive alternative text to otherwise meaningful graphics, we created an additional, visually-hidden <span> that included the alternative text of the graphic and that is exposed to screen reader users only:

<a href="..." target="_blank" class="external">

CSS Generated Content specification

<span aria-hidden="true" class="icon"></span>

<span class="visually-hidden"> (Opens in a New Window)</span>

</a>But there’s a better way to handle alternative text for CSS content today.

We can now provide alternative text for CSS-generated content directly in CSS, after a slash following the content.

According to the CSS Generated Content Module Level 3 specification:

Content intended for visual media sometimes needs alternative text for speech output or other non-visual mediums. The

contentproperty thus accepts alternative text to be specified after a slash (/) after the last<content-list>. If such alternative text is provided, it must be used for speech output instead.This allows, for example, purely decorative text to be elided in speech output (by providing the empty string as alternative text), and allows authors to provide more readable alternatives to images, icons, or text-encoded symbols.

This means that for meaningful icons, it looks like this:

a.external::after {

content: " \2197" / "Opens in a New Window" ;

}For decorative icons, it looks like this:

.disclosure-widget::before {

content: url("data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg height='24' viewBox='0 0 24 24' width='24' xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%3E%3Cpath d='m8.586 5.586c-.781.781-.781 2.047 0 2.828l3.585 3.586-3.585 3.586c-.781.781-.781 2.047 0 2.828.39.391.902.586 1.414.586s1.024-.195 1.414-.586l6.415-6.414-6.415-6.414c-.78-.781-2.048-.781-2.828 0z'/%3E%3C/svg%3E") / "";

}In non-supporting browsers, the slash syntax will invalidate the entire declaration, which means that you would need to precede the new syntax with a fallback for non-supporting browsers.

That being said, support for alt text in the content property is very good today. So unless you need to support Internet Explorer or other older non-supporting browsers, you shouldn’t need to worry about the fallback.

CSS alt text in browsers today

I created a test page (embedded below) to test and demonstrate how browsers handle alt text for CSS generated content today, and how the content is exposed and announced by screen readers.

The page contains two tables:

The first table contains examples of different types of CSS generated content,some of that content is intended to be decorative and some is intended to be meaningful. For each type, I created three instances: one without alt text (alt text not included in CSS declaration), one with non-empty, descriptive alt text, and one with empty alt text (alt text is empty but not omitted).

In the second table, I provided an HTML image for comparison. The HTML image table contains valid and invalid image references to demonstrate if and how the image’s alternative text is rendered in the browser. It also contains two instances of each of these images: one with non-empty alt text, and one with empty alt text.

Here is a video demonstrating how VoiceOver on macOS announces each of the examples in the table.

I got the same results with VoiceOver on iOS 26, and with VoiceOver on macOS when I paired it with both Chrome and Firefox on macOS.

Some observations from the above test:

- CSS images inserted using the

url()function that don’t have an alt text provided are excluded from the browser’s accessibility tree by default and are, therefore, not announced by screen readers. These are images with no alt text at all. - All images with an empty alt text value are also excluded from the accessibility tree. This is the expected behavior.

- Images with non-empty alt text are announced by their alternative text. And the alt text of the image is announced as part of the accessible name of the element.

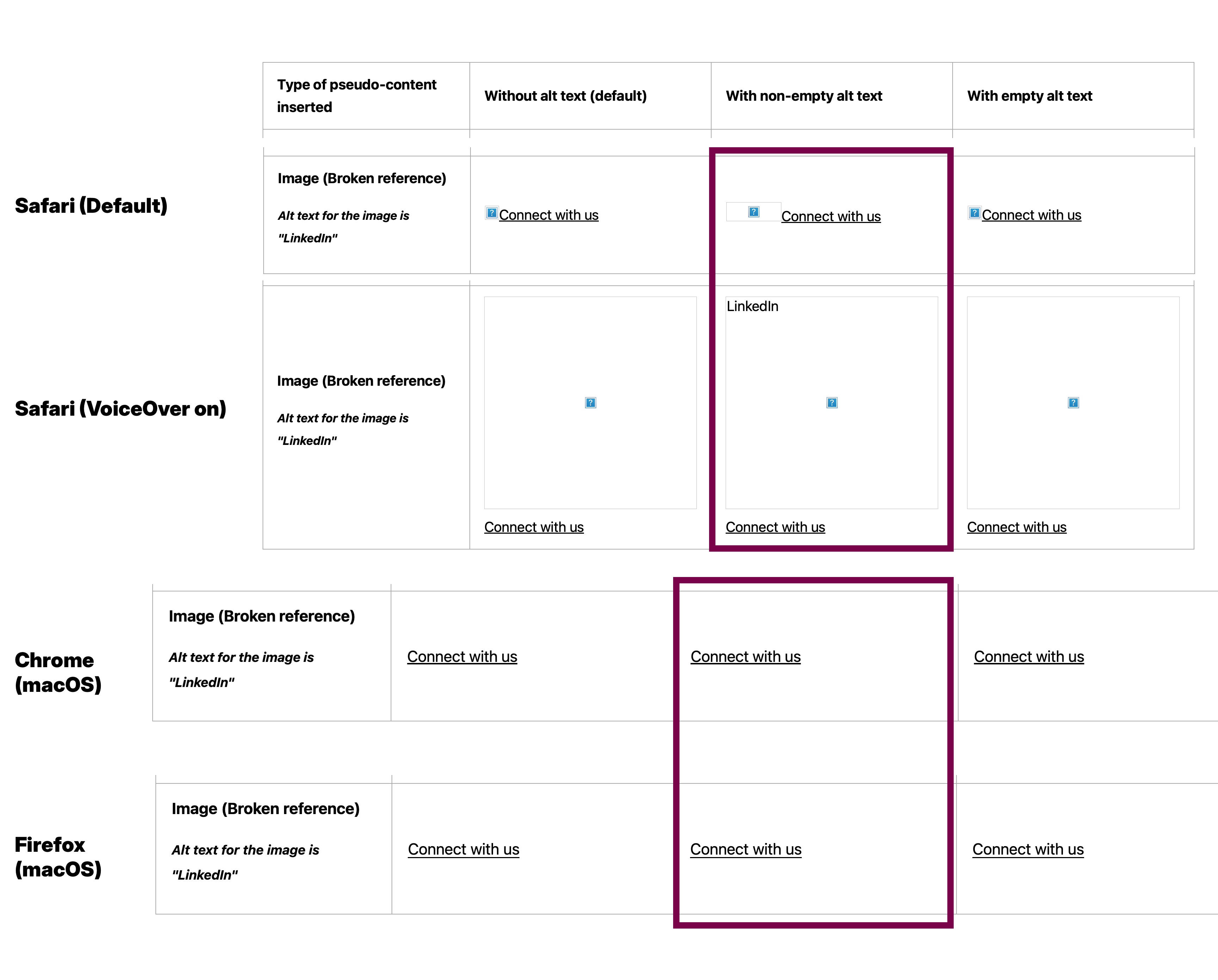

- Images with broken references and non-empty alt text are also exposed and announced by their alternative text, and the alternative text of the image is announced as part of the accessible name of the element. This is the expected behavior.

- Like images with valid references, images with broken references are not exposed when they don’t have any alt text provided.

- Emojis and unicode characters are announced by their default alternative text, except when you override the alternative text in CSS.

And finally, the alt text of a broken CSS image is not shown in place of the image when the image is not shown. The only exception on desktop is Safari on macOS which does show the alt text of the image in a large square placeholder but only when VoiceOver is turned On, or upon turning it Off.

In other words, Safari does not display the alt text of a broken CSS image by default. But if you enable VoiceOver—say by pressing CMD + F5, the broken image is replaced with a large, full-width square that contains the alternative text of the image. You can see that in action in the video recording above.

Safari on iOS 26, on the other hand, did show the alt text in the large square placeholder in my tests whether VoiceOver was On or Off.

I got very similar results with JAWS (2025) paired with Chrome (v140) and with NVDA (2025) with Firefox (v142) on Windows. The main difference from VoiceOver macOS that stood out is that NVDA announces “graphic” after the alt text of the CSS image inserted using the url() function.

NVDA paired with Chrome, however, currently does not announce the CSS alt text, as James Scholes shares in the comments. Despite the fact that Chrome exposes the alt text of a CSS image as part of the accessible name of the element it is used on, the text is not announced with NVDA, which means that screen reader users using this popular browser-screen reader combination will miss out on meaningful information.

Support for alt text for CSS generated content has improved notably since I did the same tests last year ahead of my CSS Day talk.

Last year, Chrome exposed CSS images (inserted using url()) even when they had empty alt text.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that all browsers now behave the same way in terms of exposing alt text in CSS.

Despite that, screen readers don’t all announce this alt text consistently at the time of writing.

Don’t use CSS to insert meaningful content and images

While it’s good and certainly useful that we can now provide alt text for CSS generated content, I do not recommend using CSS to insert meaningful content into the page.

Not only will some of your screen reader users miss meaningful information when the alt text is not announced by their screen reader (looking at NVDA with Chrome 👀), but there are also other reasons why inserting meaningful content in CSS is not yet recommended…

The CSS alt text is not shown when a CSS image is not rendered

The alt text of a CSS image is not shown in place of the image when the image itself doesn’t load. If the image is meaningful and it is not shown for some readon, then its meaning will be lost on most users. And the missing alt text can make interactive elements unusable by speech control users.

The non-empty alt text of a CSS image still contributes to the accessible name of the element it is used on even when it is not rendered visually. This creates a mismatch between the visible label of the element and its accessible name.

When there’s a mismatch between the visible label and the accessible name of an element, particularly when the element is interactive, it becomes more tedious for speech control users who rely on visible labels to activate controls.

Furthermore, depending on the position of the CSS image’s alt text in the accessible name, this mismatch may create an immediate violation of WCAG Success Criterion 2.5.3 Label in Name.

The alt text of an HTML <img>, on the other hand, is more likely to be shown in most browsers.

CSS Generated content does not currently translate via automated tools

CSS generated content does not currently translate via automated tools.

As Adrian Roselli notes in his article on alternative text for CSS generated content, in the future,

attr("data-alt") can potentially get around that unless you rely on automated translation tools. If you need your content to auto-translate, then the CSS approach is not for you.

CSS content is only accessible when your CSS is used

CSS content is only accessible when your CSS is used. But not all assistive technologies will render your stylesheets when displaying the page’s content. An example of an assistive technology that replaces your style sheets with custom ones is Reader Mode.

If you’re using CSS to insert meaningful content, this content will not be presented to users viewing the page in the browser’s Reader Mode or in a reading app.

CSS content is (currently) not searchable and selectable

At the time of writing of this post, CSS content is not searchable using the browser’s Find in Page functionality, nor is the generated text selectable.

If you try searching for CSS-generated text on a page, you’ll notice that the browser won’t “find” or highlight the text, even if it is present on the page. And if you try to select CSS-generated content to copy it, for example, you’ll find that you can’t. This makes CSS generated content less usable.

Note that the CSS Generated Content specification states in the Accessibility of Generated Content section that generated content should be searchable, selectable, and available to assistive technologies

(emphasis mine). So if browsers follow the spec recommendation in the future we might get different results.

So, what should you do instead?

If the content is integral to the understanding of the page, it should be in your HTML. For text content, use HTML text. For images, use an HTML <img>, and provide a descriptive alternative text in the image’s alt attribute.

If you do insert meaningful content in CSS, make sure you give it a descriptive alt text that describes its purpose.

Does this mean that alt text in CSS isn’t useful?

No, it doesn’t. Not at all!

I’ve seen arguments that because meaningful content belongs in HTML, and since you should use CSS-generated content for decorative content only, then you’ll probably never need the alt text feature.

I find the contrary to be true!

Because you should only provide decorative content using CSS, and because CSS-generated content contributes to the accName of an element, and because you don’t want that content to cause unwanted screen reader announcements, you will want to hide that content from assistive technologies in order to improve the user experience. This is where CSS alt text provides the most utility: hiding decorative CSS images and text from screen readers.

You can get really creative with CSS-generated content. CSS pseudo-elements have long been used to create visual text effects to pages, and Mandy Michael discusses an example of such effects in a blog post she wrote. As Mandy shows, hiding the duplicate text in CSS is essential, otherwise the text will be announced multiple times, resulting in a bad screen reader user experience.

Just keep in mind not to leave the alt text out when the content is decorative, otherwise it will be announced (except in the case of an image added using url()), resulting in unnecessary and unhelpful screen reader announcements.

Summary and outro

- Ideally, avoid using CSS pseudo-elements for meaningful content. Prefer using HTML.

- If you do insert meaningful content in CSS, ensure it has descriptive alt text that communicates its purpose.

- ‘Hide’ decorative or redundant CSS-generated content by giving it an empty alt text.

And remember that support may change, bugs may be fixed, others may appear, heuristics may be introduced, and things may stop working the way they have always worked. So make sure to always perform your own testing to ensure that your content and component works as expected.

Recommended reading

I wanted to keep this post short and only discuss the current state of alternative text for CSS generated content, as well as general recommendations to get the most out of this feature.

If you’re interested in learning more about any of the topics I mentioned throughout the post, consider reading these articles:

- Alternative text for CSS generated content

- alt text for CSS generated content

- The problem with data- attributes for text effects

- Voice Control Usability Considerations For Partially Visually Hidden Link Names

Continue learning

Did you know that the alt text is only one of five different ways the browser computes the accessible name of an image? For example, did you know that if the image has no alt attribute (i.e. it is omitted) and no title attribute, and the <img> is contained in a <figure> that only contains the <img> and a <figcaption>, then the browser will use the text equivalent of the <figcaption> to give the image an accessible name?

Understanding how browsers compute the accessible name of an element, and understanding what you need to do to give your images accessible names is like having accessibility superpowers. Not only will you know what to do to make your images accessible, but you will also have a toolkit of techniques at hand that you can reach for when you need to fix existing images in your codebases.

There are least three different ways to provide an accessible name to elements that are allowed to have one. What happens when multiple naming methods collide? HTML label? ARIA attribute? CSS content? And what happens when multiple naming methods collide? Which one “wins” in the accessibility tree? ⚖️

If you’re ready to stop guessing and to really understand web accessibility, then I highly recommend enrolling in the Practical Accessibility course.

Practical Accessibility is a structured curriculum that will equip you with the foundational knowledge you need to start creating more accessible websites and web applications today.

Learn more about the course and enroll at practical-accessibility.today.

Thank you for reading!